|

More

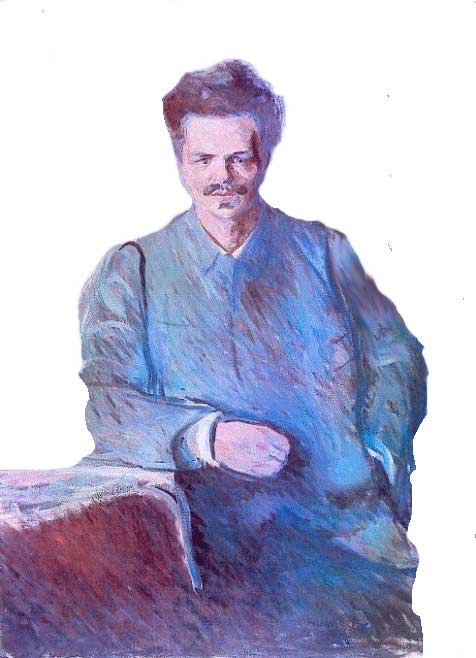

then a hundred years after his death,

Strindberg’s writing is more than a literary

heritage, his work is still engaged with and

engaging a worldwide audience. His plays are

produced across the globe, new essays and

scholarship on his person and writing are published

every year, and while his contemporaries have

returned to the shadows whence they came,

Strindberg’s name is still vivid in the public

consciousness. More

then a hundred years after his death,

Strindberg’s writing is more than a literary

heritage, his work is still engaged with and

engaging a worldwide audience. His plays are

produced across the globe, new essays and

scholarship on his person and writing are published

every year, and while his contemporaries have

returned to the shadows whence they came,

Strindberg’s name is still vivid in the public

consciousness.

His continuing influence stems not only from his

own contributions - primarily as a playwright – to

world literature, with works such as Fröken

Julie, Fadren, Dödsdansen, Ett drömspel, etc.

(Miss Julie, The Father, The Dance of Death, A Dream

Play, etc.). Nor can his position be explained

by his influence on a number of the most important

artists of the twentieth century; Antonin Artaud,

Samuel Beckett, Ingmar Bergman, Franz Kafka, Eugene

O’Neill, François Truffaut, and others.

Even the breadth of his artistry fails to explain

Strindberg's importance in the contemporary literary

world, although his paintings have received renewed

attention in recent decades and his work commands

seven digit price tags at international auctions.

Indeed, Strindberg held the auction sales record for

a work by a Swedish painter during twenty years from

1990, ahead of such established artists as Carl

Larsson and Ernst Josephson. He was finally

surpassed by Anders Zorn in the spring of 2010.

Strindberg’s writing continues to be important

because it is more than a historical legacy. More

than anything else, his work is present in our

contemporary world because of the force with which

he imbued it. He wrote quickly, intensely, and

filled particularly his prose (novels, essays, and

articles) with a restless energy and anxious pulse.

Sharp attacks and surprising reflextions are

mixed with sections of exquisitely wrought

metaphors. The narrative and the opinions may be

entertaining, amusing, irritating, poignant; but

never bland or indifferent. His books are an endless

and commanding source of inspiration.

Strindberg’s impatience drove him to leave, to

move, sometimes to foreign countries, for new

places, new people and new relationships, always

breaking social bonds. Whether his wandering was

fuelled by longing or discontent, it perfectly

reflected the time he lived in.This was a time that

saw the beginning of modernity in Sweden. Society

was in flux and Strindberg went with the flow. He

participated in the debate on gender equality,

although he alone claimed that men were the

oppressed group. He was a vocal opponent of the

lutheran state church’s control over people’s souls,

and was put to trial for blasphemy. When a modern

media industry was formed he wrote for one of the

major new newspapers, Dagens Nyheter (the

Daily News). As the labor movement developed, he

sided with them and wrote, among other political

pamphlets, August Strindbergs lilla katekes för

underklassen (August Strindberg’s Small

Catechism for the Working Class). Toward the end of

his life, when he was portrayed as an icon of the

labor movement, he had moved on again - always

radical in the original sense of the word – leaving

the political left wing behind and turned religious.

Again he was a pioneer of sorts, leaving

confrontation behind in search of peace and

prosperity, beginning the new social order of the

Swedish Welfare State, ”det svenska folkhemmet,”

where employers and employees built peace and

prosperity together.

It is perhaps appropriate that Strindberg died

before that new order had been fully established. He

was only 63, but the last photographs show him grey

and worn. He had just sold the rights to his books

to Bonniers for an impressive 200,000 SEK (which

ended up being almost 300,000 SEK, over 12 million

Swedish kronor in today’s value). The legacy he left

behind was solid. Within the next 15 years the

publisher had made almost 10 million on his

Collected Works. Strindberg would not have enjoyed

that success wholeheartedly; as Master Olof had

exclaimed forty years earlier: ”It wasn’t the

victory I wanted; it was the fight!”

|